Descent into the Marsh: Lesia Pcholka on Protest, Unity, and the Power of Visibility

Lesia Pcholka is a visual artist, born in Belarus, currently based in Berlin, Germany, and Bielsk Podlaski, Poland. She is the founder and director of the VEHA archive and was the ICORN resident in Gdańsk from 2021 to 2022.

Combining photography, video, and installation, Pcholka’s work brings together archival methods, collective memory, and historical continuity to explore how the past shapes contemporary life in Belarus and beyond.

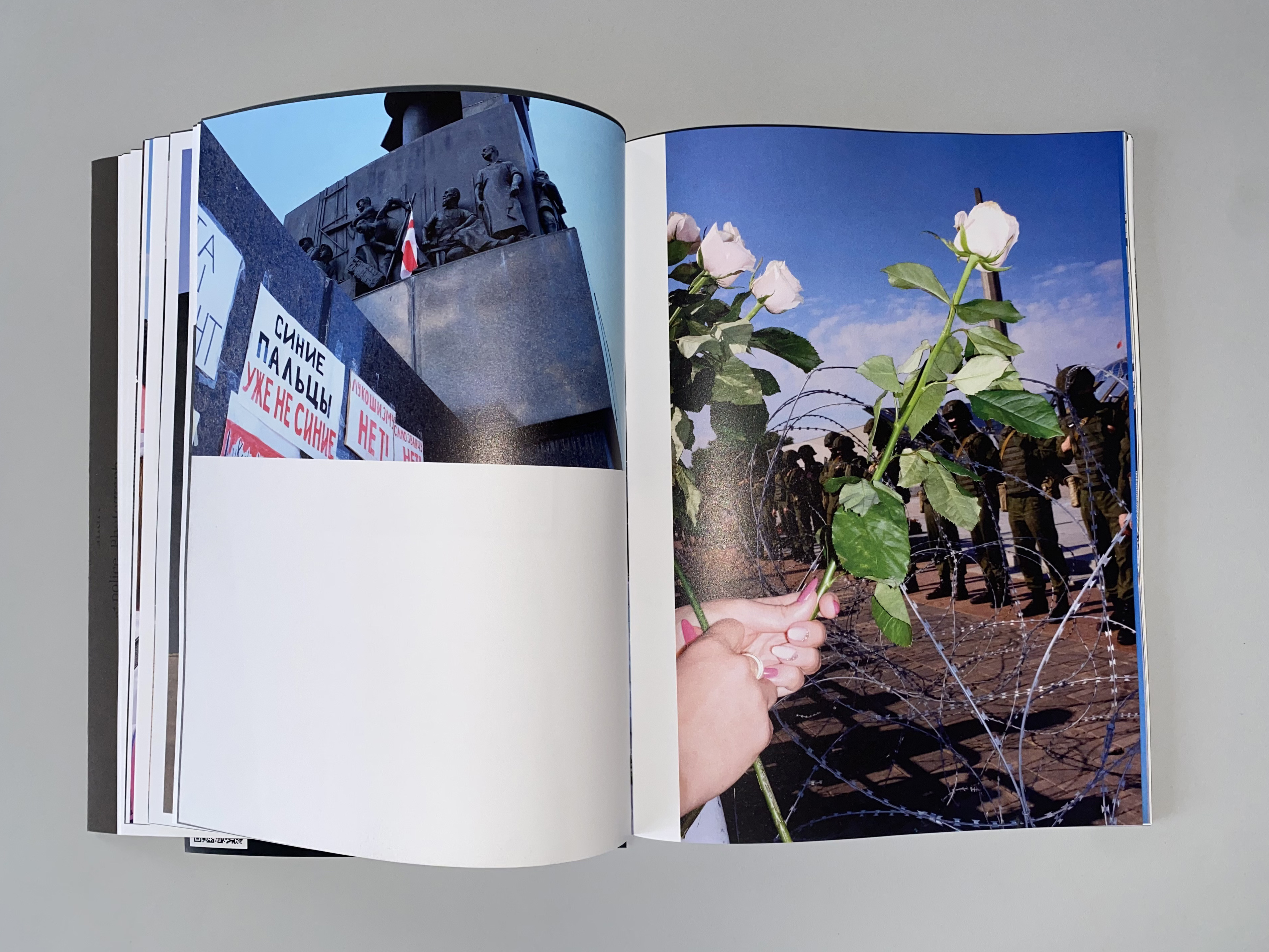

Her latest photobook, Descent into the Marsh, offers a comparative perspective on grassroots resistance and protest movements in Belarus and Hong Kong, exploring themes of unity, resilience, and dignity. The publication also examines shared experiences of repression, surveillance, and digital control.

Speaking with ICORN, Pcholka reflects on her new book, her artistic journey since completing her ICORN residency, the role of photography and art as tools of resistance in an era of artificial intelligence, and her plans.

The interview and its timely insights come just days after the Belarusian regime, on 13 December 2025, released 123 political prisoners, including opposition leaders, in exchange for the lifting of US sanctions on the country.

ICORN: As a former ICORN resident, how has your professional journey developed since finishing your residency in Gdańsk? In what ways did that experience influence your work?

Lesia Pcholka: The year I spent in Gdańsk was more than just an opportunity- it gave me hope that I would be able to continue working as an artist, even in exile. Before that, I had only had one residency and barely understood how those programmes worked or what they could offer. Gdańsk gave me a roof over my head, and that meant a lot. A gallery staff member helped me navigate the complex bureaucratic procedures- applying for a residence permit to registering as a taxpayer- things that would have been extremely difficult to figure out alone.

During that time, I created the exhibition “Weakness Street” of which I am still proud to this day. I worked with a professional curator, immersing myself so deeply in the process, probably for the first time in my life. If it hadn’t been 2022, but some other year, things might have been even better. However, when the full-scale war in Ukraine began, a lot changed. I now realize that I was in a state of depression, caused by my traumatic experience in Belarus, forced emigration, and the sudden and rapid shift in attitudes towards Belarusians in Europe. Despite the fact that many Belarusians are continuously fighting against the Belarusian regime, with a growing number of political prisoners each year, facing torture, incommunicado detention and psychological pressure, we were collectively labelled as co-aggressors in the war. Exhibitions were cancelled, projects were excluded and these developments affected me personally. First, I was deprived of my homeland, and then of my voice.

Still, I never stopped looking for new opportunities and poured everything I had into my work. I understood why discrimination happens and tried to move beyond my own pain by helping others where I could- volunteering as a translator at the Polish-Ukrainian border and other less significant activities. I didn't have time to adapt, but Belarusians have never had it easy, so there was no need to get used to it. Despite all the difficulties, the opportunities I have in exile are far greater than in Belarus- even before the large-scale repressions. This is the paradox of our culture: Belarusian culture exists in opposition to the Belarusian state. Unlike other dictatorships, the regime in Belarus thrives on a model of Soviet nostalgia where anything national or Belarusian is seen as a threat. There is a permanent hybrid war going where repression is illogical and unpredictable. You simply have to sense what you can do and cannot do. Belarusian culture essentially exists and survives in exile, which makes cancellations and restrictions especially damaging. Without external support, we will simply disappear, and Belarus will become part of Russia. Many already assume it is inevitable and that’s the problem. We shout that the situation is critical, but our voices fall on deaf ears because there's no visual evidence of pain.

Visibility for us is a form of resistance. I try to express this through my art- through the works I create. My works consider Belarus in a broader comparative context, tracing parallels with other authoritarian environments and exploring spaces of resistance. I address memory and trauma, women's history, and everyday history. In exile, my artistic practice has become more visual, with larger forms and more objects, but the themes I work with have not changes.

ICORN: Your new book, Descent into the Marsh, portrays grassroots protest movements in Belarus and Hong Kong. What common experiences of resistance do you see between these two movements? Why and how did you choose to focus on these particular examples?

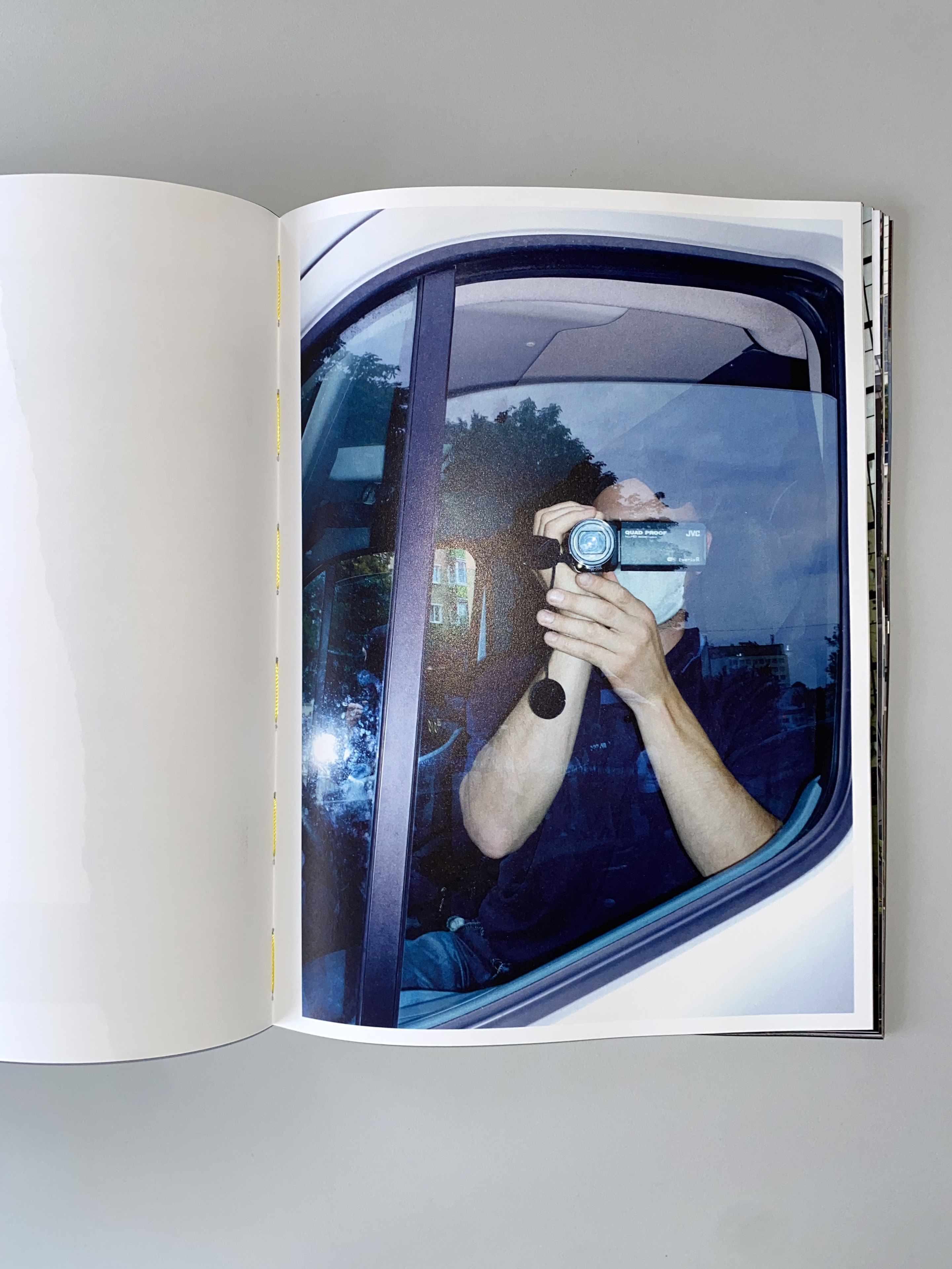

Lesia Pcholka: When working with the history of Belarus, I try not to confine myself into an exclusively Belarusian narrative. Descent into the Marsh draws a parallel between the protests of 2019-2020 in Hong Kong, and 2020-2021 in Belarus- two examples of modern revolutions which were beautiful and powerful in their essence but ultimately failed to achieve their aims. The book is structured into seven chapters illustrated by my photographs: images of the 2020 Belarusian protests, and the empty, but deeply symbolic, protest streets of Hong Kong in 2024. In the text, I draw attention to tactics and symbols: gestures of unity, the symbolic use of colour, and objects such as umbrellas that became symbols of everyday resistance. I also examine the exchange of repressive practices between the regimes in China and Belarus, with a focus on the role of surveillance technologies.

I was inspired to create this book by a Hong Kong activist whom I met during an international residency in Stockholm. He was the first person during my emigration who truly understood what I was talking about. He didn't impose stereotypes on perceptions of Eastern Europe and didn’t compare the Belarusian protest to "Maidan" in Ukraine or "Solidarity" in Poland. He grasped the meaning of resistance tactics in totalitarian countries, the strength of civil society, and what it means to live between two empires.

While neither movement achieved its immediate political goals, both have left a lasting impact on culture and society. After the protests, Belarus and Hong Kong took different paths. We are no longer alike, but our societies share a very similar trauma, and this unites us. I remain in contact with activists and sometimes receive letters from Hong Kong.

ICORN: What role do photography and art play in documenting modern resistance against authoritarian regimes, particularly at a time dominated by surveillance and artificial intelligence?

Lesia Pcholka: Photography and art play an essential role in documenting resistance to authoritarian regimes. In such systems, the language of art becomes an alternative language of politics. Photography is a document; it shows what was. Art creates a zone of semantic freedom that the authorities may attempt to control but can never fully absorb. When the state destroys documents, rewrites the past, and fabricates "historical truth," photography helps assemble society's own archive- fragmentary, but still an archive. It records not only events but also traces of presence. Photographing protests in authoritarian and totalitarian countries is not simply capturing reality; it is an act of risk. Therefore, a photographer is not only a witness but also a participant in the resistance, constantly seeking new forms of visual protection for the protesters.

This documentation is most often for the future. Right now, photographs are used against people, and many delete them to protect themselves and their loved ones. As a result, we lose evidence. In my book, I blur faces because people are still being jailed for appearing in protest photos. It's my way of preserving evidence without putting strangers in further danger.

ICORN: The book describes itself as an ‘open archive’. How does this approach shape the way we perceive unfinished social and political struggles?

Lesia Pcholka: A book is a form that can't disappear from the controlled internet. Descent into the Marsh is an open archive, containing QR codes that link to important media publications about the protests. I continue to collect new materials for my archive and plan to add them to the book later.

ICORN: What projects are you currently working on, and what are your professional plans for the future?

Lesia Pcholka: I currently live between Berlin and Poland an try to continue working as an artist. Recently, I illustrated the ICORN anthology for Willa Decjusza, creating illustrations for 10 poets currently or formerly in ICORN residence. Working at the intersection of poetry and visual art was a very interesting experience for me.

Together with a colleague, I run VEHA, an independent archive of Belarusian photography from the 20th century. We collect exclusively digital copies from family archives, conduct research, and occasionally organize exhibitions. We don't just show photos; we invite artists from different countries to create new works based on the archive. There are only two of us, but this project provides us with a foundation that keeps us going.

Sometimes I give lectures on working with memory and the history of everyday life. I would like to find a gallery interested in representing me, but I have no idea how to do that. I've never had such experience. Sometimes I feel like I am too old, sometimes too professional, sometimes not professional enough. In any case, whether you're a refugee or not, being an artist is always a risk. I am hard-working and have no shortage of ideas. I have no concrete plans for next year, but I've overcome this feeling of lack of a future- it no longer scares me.

You can find out more about Lesia Pcholka on her website.